Some time ago I blogged about a new seminary manual on the Doctrine and Covenants released by the Church. The manual is significant because it includes discussions of sensitive topics related to Church history, such as the multiple accounts of the First Vision, the Mountain Meadows Massacre and the Utah War, the history of plural marriage, and the history of the priesthood ban. It appears that by including these topics the Church is taking steps towards more transparency when it comes to its history and “inoculating” its young members who are likely to encounter antagonistic websites that can easily blindside them with these issues if they aren’t prepared.

My friend Neal Rappleye has called my attention to a new manual released this year for seminary and institute students. The manual, Foundations of the Restoration, covers early Church history and corresponding sections of the Doctrine and Covenants. “This course,” the introduction reads, “gives students the opportunity to study the foundational revelations, doctrine, historical events, and people relevant to the unfolding of the Restoration of the Church of Jesus Christ as found in the standard works, the teachings of latter-day prophets, and Church history” (v). Each lesson is divided into an introduction, background reading, suggestions for teaching, and student readings. In order to receive credit for the class (Religion 225), students “are required to read the scripture passages, general conference talks, and other materials listed in the Student Readings section of each lesson. Students must also meet attendance requirements and demonstrate competency with course material” (vi).

There are many remarkable things about the new manual, including three things that I believe are significant in light of the Church’s efforts to be transparent and proactive in discussing sensitive issues in Church history. First, the manual copiously draws from the much-discussed Gospel Topics essays. Second, the manual employs the work of the Joseph Smith Papers Project and directs students to the project’s website. Third, the manual includes statements from Church leaders on confronting doubts and questions about Church history.

I. Gospel Topics

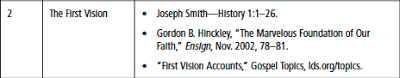

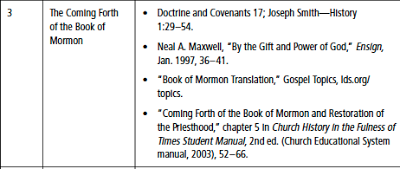

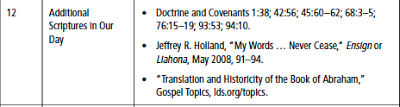

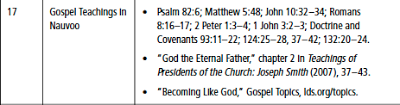

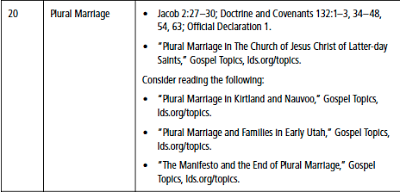

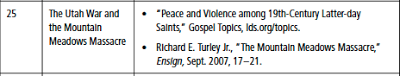

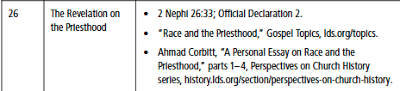

The manual directly recommends students read all but one of the Gospel Topics essays posted on the Church’s website. “Suggested Readings” for students include one of the essays dealing with the topic of the lesson (ix–xii, 138–139). As such, students are recommended to read the following essays in conjunction with the following lessons:

At the back of the manual are included unpaginated handouts for students. One of the handouts, “Understanding Plural Marriage,” is essentially a reprinting of excerpts from the Gospel Topics essays on plural marriage. The manual reprints the part of the essay “The Beginnings of Plural Marriage in the Church” that mentions Joseph Smith’s sealings to Helen Mar Kimball “several months before her 15th birthday” and “to a number of women who were already married.” Post-Manifesto plural marriages and the “Second Manifesto” are likewise noted.

In addition to the subjects discussed in the Gospel Topics essays, students will read about the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society (67), the nature of the Joseph Smith Translation, which is deemed “more of an inspired revision than a traditional translation” (51–53), Danites and the Mormon War (67–68), the events leading up to the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, including the details of the suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor and Joseph’s use of a firearm to defend himself in Carthage Jail (100–103), the succession crisis (104–109), and the role of women in the Church historically and today, including the relationship between women and the priesthood (79–83).

As can be seen, the new manual liberally employs the Gospel Topics essays as it discusses these and other sensitive issues that students are likely to encounter as they study Church history.

II. The Joseph Smith Papers

The new manual cites both the print and online versions of the Joseph Smith Papers 4 different times (12, 28, 39, 80). In the lesson on the history and importance of the Relief Society, students are encouraged to “read the minutes of early Relief Society meetings at josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/Nauvoo-relief-society-minutebook.”

III. Counsel from Church Leaders on Doubt

Finally, the new manual includes several citations from General Authorities on how to confront doubts and questions that may arise in studying Church history or when confronted by antagonistic depictions of Church history. Recent counsel from Elders Jeffrey R. Holland, Neil L. Andersen, Steven E. Snow, and President Dieter F. Uchtdorf on the subject of confronting doubt and seeking truth makes an appearance in the manual (“Lesson 10: Seek the Truth,” 42–46). Handouts are likewise prepared for students with the quotes from these Church leaders that appear in lesson 10 (“Balancing Church History” and “Discerning Truth from Error”).

As such, in addition to directly addressing the issues raised in the Gospel Topics essays, the manual also prepares students to think about how to confront questions and doubt by providing counsel from Church leaders on faith and doubt and on seeking truth.

Conclusion

The publication of Foundations of the Restoration marks further progress towards a more transparent “warts and all” type of history produced by official Church channels. It likewise signals the Church’s institutional efforts to make young Latter-day Saints aware of the issues in Mormon history that are being discussed and debated online and elsewhere. Contrary to what cynical voices on hostile parts of the web might claim, the Church is not “burying” these issues. It is not making mere token gestures of transparency to save face. It is actively striving for genuine openness and disclosure about the sensitive issues in Mormon history. The subjects discussed in the Gospel Topics essays (and, indeed, the essays themselves) are being filtered into the Church’s curriculum intended for broad consumption. The effort is thus undeniably being made by the Church to strive towards a more honest, nuanced, and, ultimately, robust history. (As if the Joseph Smith Papers didn’t already prove that!) Whether this effort (and the long-term impact this effort seems to intend) is adequate can of course be debated. What cannot be debated, however, is that claims made about some sort of institutional dread, paralysis, or conspiracy on the part of the Church when it comes to confronting and examining its history are wholly dubious and strongly contradicted by such empirical signs as the existence of this new manual.

Addendum (June 25, 2015): Some have wondered what exactly I meant by saying the Church is moving towards producing a more “transparent” history. One Latter-day Saint commenter at the Interpreter blog (where this post was cross-posted the other day) objected to my use of this language, saying that “it carries a negative and PC connotation which . . . is unnecessary.” This commenter insisted that using the language I did feeds into the critics’ (false) narrative that “the Church intentionally deceives people or has some terrible secret which will expose the whole thing as a fraud they want to hide.” I responded thusly:

This is actually a fair critique. I was hasty in my write-up of this blog post, mainly because I wanted to get it posted and on the web ASAP. I should’ve been more careful with my choice of language. Words like “transparency” and such are rhetorically-laden with all sorts of connotations that I didn’t intend. Basically, what I meant to say is this (from a follow-up guest post on my personal blog): “The reality is that there is no Church conspiracy to keep information from its members. It is true that in past decades the complexities of certain historical issues and the nuances of certain doctrinal topics were not explored in great length in Church magazines and manuals, but this was a matter of emphasis, not a cover up.”

I tried to communicate basically this in my concluding paragraph, but it looks like I failed.

I hope this clarifies things. It was not my intention to communicate the negative connotation that is attached to the word “transparency” in this context. My apologies for any confusion or for giving a wrong impression.