|

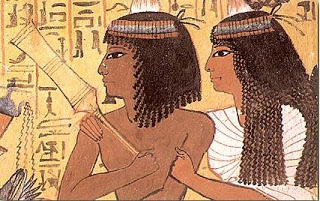

| Detail of an image inside the tomb of Sennedjem, discovered at the necropolis of Deir el-Medina and dating to the 19th dynasty. Here Sennedjem is accompanied by his wife Lyneferti and wields the “sekhem-scepter, a symbol of power.” (Image and description via Tour Egypt.) |

The German Egyptologist Jan Assmann has some interesting observations about the ancient Egyptian conception(s) of death and the afterlife in his volume Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt (trans. 2005). In one section of his book Assmann discusses how death for the ancient Egyptians was in part conceived as social isolation both here and in the hereafter. Relationships, including relationships between family members and familial generations, were meant to endure beyond the grave. Separation or isolation from the family as well as the gods was a form of death that the Egyptians combated with an phalanx of myths and rites.

“As the ancient Egyptians understood it,” writes Assmann, “a person lived in two spheres.” These spheres were the “physical sphere” and the “social sphere,” respectively. “In both spheres, the principle of connectivity worked to confer and maintain life, and correspondingly, the principle of disconnectivity threatened and wrought death” (p. 39).

Accordingly, the ancient Egyptians were obliged to maintain mortuary cults for their dead. This included not only performing careful and proper burials that equipped the dead with the appropriate funerary paraphernalia (funerary texts, amulets, shrouds, mortuary chapels, canopic jars, etc.), but also retaining the memory, dignity, honour, and especially name of the deceased through the maintenance of the funerary cult.

This, of course, is where modern people have (understandably, yet also erroneously) received the impression that the ancient Egyptians were “obsessed with death.” Actually, the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with life and resurrection, and ensuring that life (including all the perks and benefits of having a physical body) would continue eternally beyond death.

As Assmann explains, this relationship between the living and the dead not only had precedent in the mythological realm with the relationship between Osiris and Horus (the latter being obliged to maintain the funerary cult and memory of the former), but was reciprocal in nature (pp. 41–52). That is to say, “Father and son are dependent on one another. They stand by one another, the one in the afterlife, and the other in this life. Such was the form of the contract between the generations” (p. 47). As the son maintained the funerary cult of his deceased father, and thereby ensuring the memory, honour, and name of the father would endure through endless generations, the father in return would intercede for his son on behalf of the gods.

This is most clearly seen in an Abydos temple inscription commissioned by Rameses II for his father Seti I. The text includes a dialogue between the father and son that includes the following (p. 51).

First, Ramesses says:

See, I keep your name alive, I have acted on your behalf!

… May you now say to Re:

“Grant a lifetime filled with jubilee festivals to King Ramesses.”

It is good for you when I am king.

A good son is he who commemorates his father.

Seti replies:

Rejoice, my son, whom I love, King Ramesses!

…I shall say to Re with a loving heart:

“Grant him eternity on earth like Khepri!”

I repeat to Osiris, as often as I appear before him:

“Grant him double the lifetime of your son Horus!”

As such, Assmann stresses that death, at least on a metaphysical level, for ancient Egyptians included some idea of social and familial isolation. (Well-known are the wonderful Egyptian tales of the Shipwrecked Sailor and Sinhue, who both fear that their deaths in foreign, strange lands will separate them from their families and kinsfolk and will thus affect them negatively in the afterlife.) He explains:

It is easy to see that this concept of the person corresponded perfectly with the structure of a polytheistic religion. Deities, too, existed as persons in reciprocal relationships in which they acted on and spoke with one another. They were what they were as persons only with respect to one another. Constellative theology and anthropology mirror and model themselves on one another, stressing the ties, roles, and functions that bind the constituent members of the group. What they view as the worst evil are the concepts of isolation, loneliness, self-sufficiency, and independence. From their point of view, these are symptoms of death, dissolution, and destruction. Even for godhood, loneliness is an unbearable condition. (p. 57).

Little wonder, then, that, as another Egyptologist has explained, “for the Egyptians, their relationship

with spouse, siblings, parents, children, ancestors, and descendants was of greatest consequence,” and as such the Egyptians carried the “conviction that the

family structure would continue after death.” In short, Assmann contends, the ancient Egyptian mortuary cult had “the aim of reintegrating the deceased into a community that will take in the one who has been torn from the land of the living (p. 63).

All of this of course should resonate to Latter-day Saints. Drawing from the biblical tradition (Malachi 4:5–6; Hebrews 11:40), the Prophet Joseph Smith taught of “principles in relation to the dead and the living that cannot be lightly passed over, as pertaining to our salvation. For their salvation is necessary and essential to our salvation” (Doctrine and Covenants 128:15). The entire purpose (the ultimate good or summum bonum as Joseph called it [v. 11]) of temple ordinances that seal and bind generations through work for the living and the dead (by proxy) was to effect a communal exaltation for God’s children.

For we without them cannot be made perfect; neither can they without us be made perfect. Neither can they nor we be made perfect without those who have died in the gospel also; for it is necessary in the ushering in of the dispensation of the fulness of times, which dispensation is now beginning to usher in, that a whole and complete and perfect union, and welding together of dispensations, and keys, and powers, and glories should take place, and be revealed from the days of Adam even to the present time. (v. 18).

Hence the Prophet’s insistence that exaltation could only be achieved through celestial marriage, or through the creation of eternal families that would see “a fulness and a continuation of the seeds forever and ever” (D&C 132:19; cf. 131:1–4).

And why not? After all, if “that same sociality which exists among us here will exist among us [in the post-mortal world], only it will be coupled with eternal glory, which glory we do not now enjoy” (D&C 130:2), then the only anthropology and cosmology, it would appear, that could reasonably accommodate such would be ones that saw the perpetuation of families and kinships sealed together in eternal bonds.

This is of course a very hasty description of ancient Egyptian mortuary religion as well as Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo-era theology concerning the role and purpose of sealings. Much more could be said about how practices such as plural marriage and the law of adoption factored into Joseph’s sealing theology and praxis, for instance, to say nothing of the seemingly endless stream of research Egyptologists have written on almost every aspect of Egyptian funerary religion. Hopefully my description of both has been good enough to sufficiently illustrate the discernible parallels. To be sure, considerable differences in both theology and praxis exist between the two. And many of these ideas can be found elsewhere throughout the world. Ancestor worship, cults for the dead, reciprocal relationships between the living and the dead, intercession for the living by the dead, and so forth are present in many theological systems. These elements are not unique to the ancient Egyptians and modern Mormons. Nevertheless, enough parallels do exist to warrant mention and to invite consideration into how these two systems compare and contrast.

Inasmuch as Joseph Smith professed to be a restorer of primeval ordinances and lost truths, it is always exhilarating to hear faint echoes of the Prophet’s teachings in the tombs and temples of Egypt. (Just ask Hugh Nibley!) Yet another reason, I suppose, to “become acquainted with all good books, and with languages, tongues, and people” (D&C 90:15), and “to obtain a knowledge of history” (D&C 93:53).